Otway Ranges (AU)

Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

.

>Otways Habitat Campaigns

.

.

Otways Location Map

Source: Google Maps Australia

[Read Detailed Map (2004) (PDF)]

Source: Google Maps Australia

[Read Detailed Map (2004) (PDF)]

.

.

Otways Overview

Bridge Track in the Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

Bridge Track in the Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

.

Along the crest of the wettest part of the Otway Range lies a rolling plain with rounded hills and shallow valleys. This area has one of the highest annual rainfalls in Victoria, averaging almost 2000mm at Weeaproinah.

Prior to settlement late last century, tall open forests, Eucalyptus regnans (Mountain Ash) and associated species dominated the landscape, but now most areas have been cleared for agriculture.

The perennial nature of many of the creeks and drainage lines gives the area high water catchment values. Conflict also arises between its scenic appeal as a rural landscape and the conversion of farmland to softwood plantations.

Tall Timbers of the Otways

Tall Timbers of the Otways[Source: OREN,^http://www.oren.org.au/]

.

.

Otways Regions

.

(tba)

.

.

Otways Ecology

.

‘The Otway Ranges support diverse native plant communities ranging from Cool Temperate Rainforest to Heathy Woodlands. Lunt (1989) described 19 floristic communities (comprising 55 subcommunities) in the Otway FMA. Further work may define other subcommunities. Native vegetation has been mapped into one of nine major communities (refer to Section 6.1). Cool Temperate Rainforest, Heathy Woodland, Wet Heath and Coastal Complex floristic communities within State forest have been zoned for conservation. In State forest, the five floristic communities within the production zone are Wet Sclerophyll Forest, Foothill Forest, Damp Sclerophyll Forest, Grassy Forest and Dry Sclerophyll Forest.More than 30 plant species classified by Gullan et al. (1990) to be rare, vulnerable or endangered in Victoria are found within State forest in the Otways FMA. Most of these species are found within Cool Temperate Rainforest, or occupy either riparian or poorly drained sites. A significant number are ferns or fern allies.'[Source: Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (1992), ^http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/forests/regional-information/otway/otway-forest-management-plan/conservation-of-resources-and-values#6.3 Flora species of the Otways that are classificed as being national rare and therefore at risk of local extinction are:

- Cyathea cunninghamii Slender Tree-fern

- Tmesipteris elongata Elongate Fork-fern

- Burnettia cuneata Burnettia

- Eucalyptus yarraensis Yarra Gum

.

Threatening Processes across the Otways

.

- Increase in sediment input to rivers and streams due to human activities

- Loss of hollow-bearing trees from Victorian native forest

- Habitat fragmentation as a threatening process for fauna in Victoria

- Human activity which results in artificially elevated or epidemic levels of Myrtle Wilt within Nothofagus-dominated Cool Temperate Rainforest.

- Bushfire management – prescribed burning, failure to suppress wildfires, bushfire arson

Ferns, Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti,

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

Ferns, Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti,

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

.

Top Order Predators vital to maintain Biodiversity Health

.

[Source: ‘What Happens When the Top Predator Is Removed From an Ecosystem?‘, by Hayley Ames, eHow Contributor, 20110519, ^http://www.ehow.com/info_8451795_happens-top-predator-removed-ecosystem.html].

‘Top predators are the animals that occupy the position at the top of a food web. Examples of top predators include sharks and wolves. Top predators play an important role in maintaining the balance and biodiversity of an ecosystem. If the top predator is removed from the delicate balance of any particular ecosystem, there may be disastrous effects for the other plants and animals that inhabit the environment. Large Forest Owls are the top level nocturnal predators of the forest and woodland areas such as the Otway Ranges. Their continued presence in certain localities is principally dependent on the presence of suitable foraging habitat, prey species and hollow-bearing trees for roost and nest sites.’

.

Trophic Cascade

‘When a top predator is removed from an ecosystem, a series knock-on effects are felt throughout all the levels in a food web, as each level is regulated by the one above it. This is known as a trophic cascade. The results of these trophic cascades can lead to an ecosystem being completely transformed. The impacts trickle down through each level, upsetting the ecological balance by altering numbers of different animal species, until the effects are finally felt by the vegetation.’

.

Plant Life

‘When a top predator is no longer present, populations of their herbivorous prey begin to boom. Without a top predator to regulate their numbers, these animals put a great deal of pressure on the existing vegetation that they require for food and can destroy large amounts of plant life, such as grasses and trees. This then causes further problems, such as soil erosion and loss of animal habitat. Eventually, humans are also impacted due to the resulting lack of soil fertility and clean water that depend on these plants.’

Competition and Biodiversity

Another problem involving the loss of vegetation is the competition that is created between herbivorous species. Competition between species for the remaining plant life is high and weaker species lose out to stronger ones, leading to the potential loss of weaker animals, as well as plant species. Increased competition, therefore, leads to a lack of biodiversity. In contrast, top predators often have varied diets, which means they can pursue a new food source if one is running low, preventing the first source from being eradicated completely. This is one of the ways that top predators are able to maintain biodiversity and the balance of an ecosystem.’

.

Fear Factor

‘The presence of a top predator also helps to maintain balance in an ecosystem by influencing the behaviour and movements of its prey through the fear of being caught. Animals that are prey to a top predator will move around in order to avoid it. This prevents plants and animals in any particular area of an ecosystem from being over-consumed, preserving food sources and habitats. In the absence of top predators, this regulation disappears, allowing certain areas of vegetation to be destroyed completely.’

.

.

Otways Wildlife

.

The Otway Ranges includes featured species considered significant due to their known low number or restricted habitats as a consequence of decades of logging and associated habitat fragmentation and destruction. Significant fauna species include:- Tiger Quoll (Dasyurus maculatus)

- Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus)

- Yellow-bellied Glider (Petaurus australis)

- Common Brushtail Possum (Trichosurus vulpecula)

- Smoky Mouse (Pseudomys fumeus)

- Yellow-bellied Sheathtail-bat (Saccolaimus flaviventris)

- Great Pipistrelle (Falsistrellus tasmaniensis)

- Sugar Glider (Petaurus breviceps)

- Feathertail Glider (Acrobates pygmaeus)

- New Holland Mouse (Pseudomys novaehollandiae)

- Swamp Antechinus (Antechinus minimus)

- Broad-toothed Rat (Mastacomys fuscus)

- The Common Bent-wing Bat (Miniopterus schreibeisii)

- Swamp Skink (Egernia coventryi)

- Blue-winged Parrot (Neophema chrysostoma)

- Rufous Bristlebird (Dasyornis broadbenti)

- Beautiful Firetail (Emblema bella)

- Pink Robin (Petroica rodinogaster)

- Masked Owl (Tyto novahollandiae)

- Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua)

- Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)

- Grey Goshawk (Accipiter novaebollandiae)

- Australian Hobby (Falco longipennis)

- Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus)

- Gang-gang Cockatoo (Callocephalon fimbriatum)

- Australian King Parrot (Alisterus scapularis)

- Ground Parrot (Pezoporus wallicus)

.

[Source: Otway Forest Management Plan, June 1992, ^http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/forests/regional-information/otway/otway-forest-management-plan/conservation-of-resources-and-values#6.3, Read More].

Other fauna species found in the Otways include:- Long-nosed Potoroo (Potorous tridactylus tridactylus)

- Southern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus)

- White-footed Dunnart (Sminthopsis leucopus)

.

Threatened native species and ecological communities in the Otways

- Cool Temperate Rainforest Community

- Slender Tree-fern

- Tiger Quoll

- Tall Astelia

- Australian Grayling

- Powerful Owl

- Tasmanian Mudfish

.

.

Habitat Threats

.

.

.

Otway’s Threatening Processes

.

-

Increase in sediment input to rivers and streams due to human activities

-

Loss of hollow-bearing trees from Victorian native forest

-

Habitat fragmentation as a threatening process for fauna in Victoria

-

Human activity causing heightened risk of Myrtle Wilt disease

.

Myrtle Wilt disease killing ancient and rare native Myrtle Beech trees (Nothofagus cunninghamii) across the Otway Ranges

http://www.australianpaper.forests.org.au/docs/recentplantphotos2.html

Myrtle Wilt disease killing ancient and rare native Myrtle Beech trees (Nothofagus cunninghamii) across the Otway Ranges

http://www.australianpaper.forests.org.au/docs/recentplantphotos2.html

.

Arguably, we may consider that of the above twenty-seven possible categories of Habitat Threat, the following still remain for the Otway Ranges.

Threats from Bushfire

Threats from ‘Darkside’ Ecologists

Threats from Deforestation

Threats from Development

Threats from Dumping

Threats from Farming

Threats from Ferals & Predators

Threats from Fishing

Threats from Government Funding Neglect

Threats from Government Mismanagement and Wastage

Threats from Greenwashing

Threats from Groundwater Tampering

Threats from Mining

Threats from Native Pet Industry

Threats from Human Overpopulation

Threats from Poaching and Poisoning

Threats from Pollution

Threats from Public Land Sales

Threats from Road Making

Threats from Sewage

Threats from Stormwater Runoff

Threats from Tourism and Recreation

Threats from Utility Corridors

Threats from Weak Conservation Laws

Threats from Weeds

.

Otway Habitat Loss threatening Native Forest Owls

Barking Owl (Ninox connivens)

Barking Owl (Ninox connivens)

.

The old growth Mountain Ash temperate forests of the Otway Ranges provide a vital but restricted habitat to Australia’s largest forest owls such as the Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua), the Barking Owl (Ninox connivens), the Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae), the Sooty Owl (Tyto tenebricosa) and the Southern Boobook Owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae). These are collectively referred to as the Large Forest Owls. These owls are all forest dwellers, but vary in micro-habitat requirements and general ecology. Owls are monogamous, forming life long pair bonds and are generally sedentary, occupying large permanent home ranges. Each pair of these Large Forest Owls require a permanent territorial home range of up to around 1000ha (1km2) and more if the quality of habitat and density of prey is poor. They each tend to have small population sizes due to low reproduction rates, high juvenile mortality, large home ranges and decreasing areas of habitat.

.

Threats to Survival

- Habitat clearing and fragmentation

- Removal of tree hollows

- Bushfires and/or non-prescribed bushfire regimes.

.

Required Conservation Actions

- Long term habitat management approaches should be directed towards maintaining connectivity within and between large patches of forest to link areas of suitable habitat and to ensure the protection of prey by maintaining understorey and ground cover habitat within bushland areas.

- Support protection and management of bushland containing owl species.

- Encourage and plan for tree retention, particularly habitat trees on private land.

- Revegetation of riparian and creekline habitats, for movement and foraging opportunities.

- Retain old growth forest, including the ground cover, such as fallen logs to maintain habitat for prey species.

- Increase community awareness and involvement in owl conservation of the community through local environment network.

.

[Source: ^http://www.gosford.nsw.gov.au/environment/plants-animals/threatened-species/large-forest-owls].

More Research Required

‘A much greater effort needs to be made to collect basic demographic data for owl populations in different environments. the establishment of regional owl monitoring programmes is needed. These would provide a focus for collecting long-term demographic data and should also be implemented to track long-term changes in population levels. the rol eof nest-boxes for use in owl research in Australia needs to be investigated.’

‘Do owls still nest, roost and forage preferentially in riparian zones if the landscape is comprised of a much higher proportion of tall, moist forest? Specific details of owl nest sites, roost sites and diets in different environments and vegetation types are still unknown.’

.

.

Powerful Owl

Powerful Owl

(Australia’s largest owl, measuring up to 60cm (head to tail) )

^http://bambarard4np.blogspot.com/

Powerful Owl

(Australia’s largest owl, measuring up to 60cm (head to tail) )

^http://bambarard4np.blogspot.com/

.

Powerful Owls Habitat & Ecology

There is a strong relationship between the occurrence of Powerful Owls and their habitat. They are forest dwellers which rely on areas of old growth forests that contain mature, live hollow bearing eucalypt trees that can be hundreds of years old. In a study of Powerful Owls near Melbourne, McNabb (1996) found a connection between habitat quality, home range size, diet breadth and breeding success with owls in less productive habitat occurring more sparsely and breeding less successfully on a more generalised diet. Optimum habitat elements for fostering high breeding productivity, include high densities of large, live (old growth 150+ years) hollow bearing trees in sheltered positions and orientations.

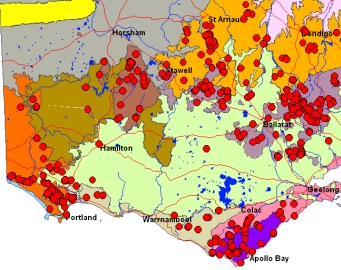

Distribution of Powerful Owls in and around the Otways

(South West Victoria Bioregion)

[Source: Victorian Fauna database 2005

^http://bird.net.au/bird/index.php?title=Powerful_Owl]

Distribution of Powerful Owls in and around the Otways

(South West Victoria Bioregion)

[Source: Victorian Fauna database 2005

^http://bird.net.au/bird/index.php?title=Powerful_Owl]

.

The Powerful Owl occurs along the south-eastern fringe of mainland Australia from southern Queensland into New South Wales and Victoria. In Victoria it occurs across the eastern highlands extending into south-west Victoria. Most records occur in forested areas, in the south-west records exist in the following biorgeions; Central Victorian Uplands, Goldfields, Greater Grampians, Glenelg Plain, Otway Ranges, Otway Plain and Warrnambool Plain.

Modelling the distribution of Powerful Owls in Victorian forests by Loyn et al (2002) found that…

‘Powerful Owls favour the drier forest types which have many live hollow bearing eucalypt trees in association with Blackwood Wattles, diverse habitats and extensive mature forest within 2 to 5 km’

.

Powerful Owls may share tracts of forest with Sooty Owls and Masked Owls, but habitat modelling data suggest that Powerful and Sooty Owls have different requirements despite a broad overlap in distribution.

Powerful Owls favour the more open forest and broad gullies, with plants such as Blackwood Wattle whilst Sooty Owls favour the wetter sites and rainforest with plants such as Silver Wattle, Blanket-leaf and Tree-ferns (Loyn et al 2002). There is virtually no overlap between diets of Powerful Owl and Masked Owl, as they tend to forage in different places and take different prey. The Powerful Owl hunts for prey that almost exclusively lives in trees and mostly takes prey which is 50-100% of its own body weight whereas the Masked Owl takes smaller prey which is 3-20% of its body weight (Kavanagh 2002).

The powerful owl is a generalist hunter, preying on the most available prey at a given site and in a given season (Cooke et al 2006). The main component of the Powerful Owl diet across its range is Ringtail Possum, this may be supplemented by other arboreal possums and gliders depending on the geographic location and prey present, eg Greater Glider, Brushtail Possum, Sugar Glider, Yellow-bellied Glider (Cooke et al 2002).

The extent of home range of the Powerful Owl is influenced by habitat quality and subsequently the abundance of prey. In areas near Ferntree Gully, east of Melbourne where there was good habitat (since destroyed by logging and Melbourne suburban sprawl) and an abundance of Ringtail Possum prey the home range was estimated to be 300ha (McNabb 1996), for areas in the Box-Ironbark forests of Victoria the home range could be from 1380 to 4770ha (Soderquist et al 2002), but it is generally accepted to be about 1,250 ha or within a 2 kilometres radii (Loyne et al 2002).

Nest sites are selected high up in old, large living eucalypts (150 + years old). Nest hollows are large and can be about 1metre deep with an entrance nearly .5 m wide (Cooke et al 2002). Owls may sometimes re-use nest sites or select a different hollow every 2-4 years. In Victoria it has been observed that laying takes place late May to a peak mid June with a nestling period 8-9 weeks during which one or two chicks are reared, post fledgling dependence lasts for 6-7 months (McNabb 1996).

.

Powerful Owls – habitat threats:

- Loss of suitable large hollow bearing trees which has a direct impact on the availability of nest sites and also reduces habitat that supports arboreal marsupials which comprise the majority of the owl’s diet. [deforestation]

- Processes such as fire, clearing and thinning* may lead to the direct loss of habitat trees or changes to the surrounding forest structure which may compromise the value of nest sites. Continual changes to forest structure may also reduce the availability of habitat for prey species such as Possums. Continual forest disturbance may also compromise the growth of replacement old growth (150+ years) trees which may never reach full maturity. [bushfire, deforestation]

- Loss of canopy vegetation may exposes mature eucalypts and render nesting sites unsuitable. Wide spread and frequent fuel reduction burning may thin out thickets of vegetation that support Ringtail Possums and other prey. [bushfire, deforestation]

.

Powerful Owls – required conservation actions:

- Creation of new reserve areas such as the expansion of the Great Otway National Park will add security to Powerful Owl habitat. Powerful Owl Management areas (POMAs) have been identified across a variety of Crown land tenure to protect Powerful Owl habitat. For State Forests where clear-fell harvesting is used, areas of suitable habitat of at least 500ha (dependent on habitat type) are protected as SPZ within a 3.5km radius. Where selective harvesting is used, POMAs comprise Special Management Zones of about 1,000 Ha. In existing conservation reserves POMAs contain at least 500ha of continuous suitable habitat.

- The number of POMAs identified for each forest management area in FFG Action Statement are: Horsham 15, Portland 25, Midlands 25, Otways 15. (DSE 2004) Areas of private land that support Powerful Owls require protection with landholder support and through identification in municipal planning schemes.

- Specific Actions from the DSE Actions for Biodiversity Conservation database Midlands, Otways, Horsham & Portland Forest Management Areas Undertake owl surveys as part of the West Regional Forest Agreement to improve estimation of population size and the location of breeding population.

- Monitor at least 10% (ie 50 sites throughout Victoria) of Powerful Owl Management Areas (POMAs) regularly to determine persistence of owls and breeding success.

Protect Powerful Owl habitat in State forest according to the prescriptions in the FFG Action Statement.

.

[Source: South West Integrated Flora & Fauna Team, ^http://bird.net.au/bird/index.php?title=Powerful_Owl].

.

Otways Conservation Organisations

.

[1] Otway Ranges Environment Network, ^http://www.oren.org.au/‘OREN formed in 1996 with the aim of stopping the practice of clearfell logging biodiverse native forest (on public land) in the Otways. After an intense eight year campaign followed by a six year logging phase out period, this outcome was achieved. The OREN/Otway campaign was strongly based on the politics of non violent direct action. Thanks to the work of conservationists and Otway residents, working though the OREN “network”, all clearfell logging of native forest on public land in the Otways came to an end in 2008.’

.

[2] The Cape Otway Centre for Conservation Ecology, ^http://www.capeotwaycentre.org/‘The Cape Otway Centre for Conservation Ecology is an independent, non-profit ecological research and wildlife rehabilitation centre dedicated to the conservation of biodiversity. We achieve this through innovative and effective responses to the challenges and threats that ecosystems and species face. In addition to addressing local and regional conservation needs, much of our research contributes to widespread universal solutions.

The Centre is located in a unique region of significant conservation importance – from the heath lands, sheltered coastal inlets and cliff tops along the Great Ocean Road, to peaceful woodlands, majestic tall forests and pristine rainforest gullies. These are the habitats of some of the most intriguing animals on earth; a myriad of indigenous species including 174 species which are known to be rare or threatened and some of which are found nowhere else in the world. Since wildlife and habitats are not restricted within reserve boundaries we work across the landscape to achieve meaningful conservation outcomes.’

.

[3] Otway Agroforestry Network, ^http://www.oan.org.au/

‘The Otway Agroforestry Network encourages and supports local farmers to design and implement revegetation projects for the reasons that matter to them. Otway landholders want trees on their farms to shelter stock, control erosion and dryland salinity, attract native birds, enhance property values and, if at all possible, to generate income.

Set up by local farmers with government support in 1993, the Otway Agroforestry Network is a not-for-profit community organisation striving to encourage the wider adoption of commercial vegetation management as an integral component of more productive and environmentally sustainable farming. We are fortunate that the Federal and State Governments, along with the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, recognise the public benefits that our trees provide the community. Improved water quality in our streams, the conservation of our unique flora and fauna and the promise of alternative timber sources, make well managed trees on farms a good story for rural communities and the nation as a whole.’

.

[4] The Cape Otway Centre for Conservation Ecology, ^http://www.capeotwaycentre.org/.

[5] ANGAIR, ^http://www.angair.org.au/.

‘ANGAIR (Anglesea, Aireys Inlet Society for the Protection of Flora and Fauna) is dedicated to protecting our indigenous flora and fauna, and to maintaining the natural beauty of Anglesea and Aireys Inlet and their local environments. It was established in 1969 through the influence of a local resident Mrs Edith Lawn.’

.

[6] Anglesea Coast Action[7] Apollo Bay Landcare Group

[8 ] Barongarook Landcare Group

[9] Birregurra Community Group

[10] Southern Otway Landcare Network

[11] Conservation Volunteers Australia

[12] East Otway Landcare Group

[13] Framlingham Aboriginal Trust

[14] Friends of Bannockburn Bush

[15] Friends of Bay of Islands Coastal Park

[16] Friends of Coastal Reserve Aireys Inlet

[17] Friends of Deans Creek

[18] Friends of Painkalac Creek

[19] Forrest Landcare Group

[20] Gerangamete Flats Landcare Group

[21] Hordenvale Glenaire Landcare Group

[22] Lake Modewarre Catchment Group

[23] LorneCare

[24] Murroon Landcare Group

[25] Newfield Valley Landcare Group

[26] Friends of Moggs Creek

[27] Friends of Otway National Park

[28] Friends of Eastern Otways (Great Otway National Park)

[29] Friends of Port Campbell National Park

[30] Friends of Queen Park

[31] Geelong Field Naturalists Club

[32] Heytesbury District Landcare Network

[33] Otway Barham Catchment Landcare Group

[34] Pirron Yallock Creek Catchment Landcare Group

[35] Port Campbell Environment Group

[36] Surfers Appreciating the Natural Environment

[37] Timboon Bushland Co-operative

[38] Timboon Field Naturalists Club

[39] Upper Barwon Landcare Group

[40] Wathaurong Aboriginal Cooperative

[41] Wongarra to Wye Landcare Group

[42] Otway Coast Committee

[43] Great Ocean Road Coast Committee [44] The Forest Letter Watch ^http://www.forestletterwatch.org/ [45] The Forest Letter Watch (old archival site) ^http://www.lexicon.net/~lis01101/ [46] Geelong Environment Council, ^http://www.environmentvictoria.org.au/content/geelong-environment-council

.

.

>Otways Conservation Background

.

.

Habitat Resources

.

01 Policies

.

02 Strategies

.

03 Assessments and Reviews

.

04 Plans

.

05 Reports

.

06 Further Reading

.

[1] Beech Forest Species List of the Otways , ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicthreatenedlist.pl?wanted=fauna#birds_vulnerable [Read More].

.

Billabong, Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti

Billabong, Otway Ranges

Photo supplied courtesy of Joe Mortelliti

^http://www.redbubble.com/people/mortelliti